Today, gun hipsters around the world embrace a common creed.

It binds us. It inspires us. It gives us purpose. And while there is no formal canon to define this unspoken sense of ideological unity, it can be summarized as follows:

Guns with rollers kick @ss, bro.

So, with that poignant truth clear in our minds…

Let’s look back through the history (hipstery?) of roller-locked and roller-delayed firearms—from the MG-42 to the HK P9S—to understand their origins, their functionality and their cherished place in the hearts of gun hipsters. Because we never truly know who we are…

Until we understand where we come from.

Watch my YouTube video on roller-operated firearms, here!

The MG-42: Roll Out

It all started in 1937.

The Wehrmacht needed a new machine gun to replace their (sometimes) temperamental MG-34s. Because if there’s anything that can throw a wrench in the proverbial gears of world domination… it’s moody machine guns.

Obviously, the thing had to be reliable. It also had to withstand a high rate of fire. And while existing machine-gun actions (e.g., Browning, Maxim/Vickers, etc.) could have probably satisfied those requirements…

It also had to be cost effective for mass production. Which the MG-34 wasn’t, thanks to its old-school machined receiver.

So, instead of a sliding block, a toggle lock, or the MG-34’s rotating bolt system, Werner Gruner—lead engineer at GrossFuss AG—designed a unique “roller-locking” mechanism to facilitate linkage between the barrel and the bolt. It functioned smoothly. It functioned reliably.

But, more importantly, Gruner’s roller-based action absorbed/distributed recoil energy more efficiently than other locking mechanisms.

This helped minimize the stress imparted to the receiver while firing. Thus, the entire chassis of the gun could be made from inexpensive stampings as opposed to machined forgings.

Interestingly, a somewhat similar—but unrelated—roller-locking concept had been patented in Poland, a few years earlier. Not that German leadership would have really cared about Polish IP rights, in the late ‘30s.

In any case…

Gruner’s design became the first actual implementation of a roller-locked action in a firearm. The Wehrmacht adopted it as the infamous MG-42 machine gun in—you guessed it—1942.

Note: the MG-34 does actually use rollers in its action, but not to facilitate locking.

With that “hipstorical” context in mind, let’s look at how an MG-42-style action… rolls.

Roller-Locked Operation: Lock & Roll

I don’t own an MG-42. Because I’m in marketing. And that’s not a career conducive to owning historically relevant machine guns.

Sigh.

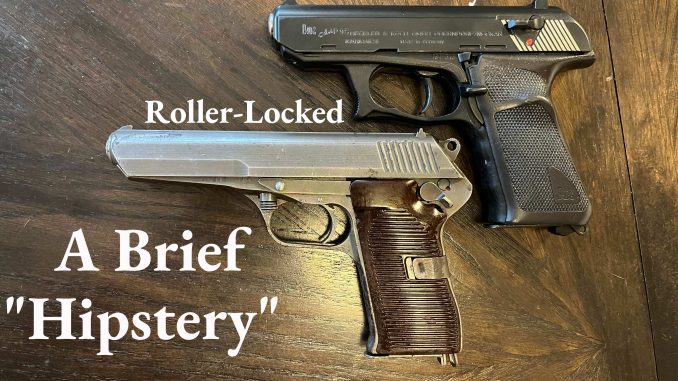

But I do own a CZ-52—which is basically a Czechoslovakian “mini-me” version of the MG-42. And while the orientation of certain components is flipped around to work in a pistol format, the general concept is the same.

Plus, I can show you pictures of my CZ-52. Since I… umm… have it.

So, then…

You’ve got a retracting barrel that’s mechanically locked to the slide—pretty typical for most locked-breech actions. But with the CZ-52, you’ve got cylindrical rollers that stick out on the slides of the barrel and nest into little nooks on the inside of the slide.

In battery, the rollers are fully captured in these nooks. This is what “locks” the barrel to the slide. Under recoil, the barrel moves back WITH the slide, until the rollers get diverted inward, out of their nooks… which unlocks the action and allows the slide to cycle.

If you know how the Beretta 92/Walther P38 falling-block system works, it’s not hugely different in terms of the general idea. But instead of a tilting wedge that hooks into recesses in the slide… the rollers kinda do that. And instead of tilting out of the way to disconnect the barrel from the slide…

The rollers, well, they roll out of the way.

Along precisely sloped channels/ramps that lead inside the barrel trunnion (which, as far as I can tell, is a fancy word for a “blocky thing” on the back-end of the barrel). Again, the CZ-52’s roller setup is kind of a mirror image of the MG-42’s setup—but they employ the exact same locking dynamics.

I’ll say the CZ-52 is a remarkably soft shooter—even when it’s cooking off Tokarev rounds at >1,500 FPS. The rollers definitely give you a smooth, plush feel as the gun cycles. Mine’s not that accurate because it’s got some corrosion in the bore, but it’s fun as hell to shoot and it’s been 100% reliable. I’ll do a review of the CZ-52 on hipstertactical.com, at some point.

But…

Before we get ahead of ourselves, we need to go back to the end of the World War II. Because some enterprising engineers at Mauser were discovering a whole new way to roll.

And they didn’t even know it.

Mauser’s Accidental Discovery

By 1944, Mauser was hard at work trying to make a cheaper, easier-to-build version of the Sturmgewehr-44 (StG-44). Because, you know, more assault rifles = less utter defeat.

Or something like that.

The StG-44 used a fairly complex tilting-bolt mechanism, driven by a gas piston. From a manufacturing standpoint, it was expensive and labor intensive. So, two guys at Mauser—Ludwig Vorgrimler and Wilhelm Stahle—had the idea to replace the tilting-bolt with an MG-42ish roller mechanism. Which would, in theory, be simpler.

However, unlike the MG-42, this design would use a fixed barrel (like the StG-44)—which makes it a very different animal.

They devised a telescoping bolt-head setup, kinda like you find in an AR-15. In other words, the tip of the bolt slides in/out of a bolt carrier. However, instead of rotating to lock/unlock, this thing had rollers on the sides of bolt head to lock everything up. The gas system would provide the energy to drive the BOLT CARRIER back, leaving the BOLT HEAD locked up against the breech for a split second… until the rollers disengaged from their locking nooks.

However, when they started testing it, they noticed something:

The bolt carrier would sorta “bounce back” when the bolt head slammed closed… and the rollers would kinda disengage on their own. So, in essence, the thing was unlocking itself.

WITHOUT the needing the gas system to do it.

That’s when Mauser’s on-site mathematician—Dr. Karl Maier—said: “Hold up, let’s try it without the gas system.” Likely preceded with “halten mien bier.”

Lo and behold, it worked. And it led to a prototype known as the “Sturmgewehr-45.”

While the StG-45 never went into production, its unique roller-based mechanism carried over into the Spanish CETME rifles of the 1950s and basically all of HK’s mid-century offerings—including the G3 rifle, the MP5 submachine gun and the P9S pistol. The system came to be known as the “Roller-Delayed Blowback” action—or, sometimes, the “Vorgrimler” action.

So, here’s my best “non-engineering-y” breakdown of how it works…

Roller-Delayed Operation: Slow Your Roll

Unfortunately, I don’t have a CETME, a G3/HK91 or an MP5.

Sigh.

But I do have an HK P9S (hooray!). Which—as noted above—uses pretty much the exact same system as all of the aforementioned guns. Only smaller.

Here we go…

Again, think of an AR-15 bolt/carrier setup: You’ve got a bolt carrier + a telescoping bolt head, but you’ve got rollers on the sides of the bolt head. In battery, the rollers are pushed out so they nest into “nooks” on two fork-like extensions, running off the back-end of the barrel.

When the recoil cycle begins, gas pressure pushes back on the bolt head. But most of the force bears on the rollers, which get smushed HARD into their nooks. This prevents the bolt head from moving back for a split second (hence the “delay”) while also transferring force inward via rollers.

This inward pressure bears against a wedge-shaped “protrusion” that’s attached to the bolt carrier (said “protrusion” fits inside the bolt head). This drives the BOLT CARRIER back while the BOLT HEAD is still impinged by the rollers. By the time the BOLT HEAD pulls away from the breech, the chamber pressure has dropped and the slide/bolt can safely complete its cycle.

In essence, the rollers transfer force around the bolt head, so the carrier can start moving back slightly before the bolt head itself.

It’s that wedge-shaped thingy that makes this possible.

From what I’ve read, lots of R&D went into calculating the optimal geometry for the wedge (as far as how much of a slope/angle was needed to make it consistent, reliable, etc.).

And that’s really the definitive difference between roller-delayed and roller-locked. In a roller-delayed setup, the rollers sit ON the sloped surfaces of the wedge when it’s in battery. So, as soon as you get pressure on the system, the rollers start squeeeeeezing the wedge (and the carrier) backward, while also keeping the bolt head in place for a moment. In a roller-locked system, the rollers are fully captured between straight surfaces, UNTIL the barrel moves back to a certain point.

Whew.

Now back to some history…

Have Rollers, Will Travel

After the war, Ludwig Vorgrimler moved to France where he helped develop the CEAM Modele 1950 prototype—which was basically a rebranded StG-45. After the French abandoned that project (because of the escalating _hit storm in Vietnam), Vorgrimler ditched France for Spain. Between siestas, paella and flamenco lessons, he worked with the Centro de Estudios Técnicos de Materiales Especiales (CETME) to continue his work on roller-delayed rifles.

By 1954, the CETME-A rifle—based heavily on Vorgrimler’s CEAM/StG-45 design—reached limited production. And while it saw some service with Spain, it was chambered in the weird 7.92×41 CETME cartridge (which used an aluminum core to achieve insanely long range and low recoil). But I guess Franco decided Spain had to be NATO compliant. Which 7.92×41 wasn’t.

Meanwhile, back in West Germany…

What remained of Mauser after WWII was essentially reborn as Heckler & Koch. So, HK’s founders knew Vorgrimler and—presumably—about his partnership with CETME, in Spain. In an indirect way, I think HK had some sense of intellectual ownership of the roller-delayed concept; many of HK’s engineers had worked in Mauser’s R&D department, where the idea originated.

So, HK partnered with Vorgrimler to get the CETME rifle beefed up for 7.62 NATO. In 1958, Francoist Spain formally adopted this “HK-ized” version of the rifle as the CETME 58 (internally known as the CETME-C). In 1959, West Germany adopted the CETME-C as the G3, which would be produced under license by HK in Oberndorf.

HK Keeps Things Rollin’

After the G3, I feel like HK’s main solve for any engineering challenge was: “Let’s put rollers in it!” And—to their credit—that approach worked. Very well.

In 1966, they introduced the MP5 submachine which used a miniaturized version of the G3’s system. By the early 1970s, they had gotten the Vorgrimler action so precise, they were able to cram into a handgun—which led to the phenomenal P9S pistol.

In the ‘60s and ‘70s, the MP5 and P9S were arguably the best weapons available in their respective classes. They both earned a reputation for unimpeachable reliability, durability and unparalleled accuracy. Even today, they’re both tough to beat in terms of natural, intuitive shootability.

Case and point…

I’ve shot an MP5. I own a P9S. They’re both like ballistic butter. Smooth. Soft. Yet, uniquely direct in terms of the recoil impulse. The fixed-barrel design makes every shot feel close and connected—while the roller-delayed mechanism filters out the abrasive feel you often get with a straight-blowback action.

Check out my in-depth review on the HK P9S, titled 9mm Nirvana to learn more about this one-of-a-kind pistol. There’s really nothing else like it, that I’ve experienced.

By the end of the 1970s, HK moved away rollers in pistols, with the infamous P7—which still used a delayed-blowback system, but with a gas piston instead of rollers. However, the MP5 and the G3 remain in service and in production to this day. Though the G36 did replace the G3 as the primary German service rifle, back in the 1990s. In the past few years, the HK 416 began entering service with German forces, as the G95.

In Conclusion

Do we “need” rollers in firearms?

“Need” is a funny concept. Especially when you’re talking to gun hipsters. About guns.

In terms of objective metrics, there’s nothing a roller-based action can do that a tilt-barrel or a gas-operated bolt can’t. But the passion—and the sense of connection—we feel for certain firearms doesn’t happen on paper.

It happens in our hands. It happens at the range. And it happens every time we shoot the gun and say, “Damn. This thing kicks @ss.”

So, if you want a weapon that always gives you those feel-good, kick@ass vibes… get yourself a gun with some rollers.

Thanks so much for reading.

Visit hipstertactical.com for in-depth reviews on cool guns.

Watch the companion video to this article, on YouTube:

Are you a gun hipster? Find out, here.

Uh Based Rolley Bois